Transition to sustainable urban mobility

Project type: Transport

Scale: Regional

Overview

The following is the (English) summary of a report written for the Flemish Government on a ‘transition to sustainable urban mobility’.

The Compass helped set the research themes and to frame the evaluation of the case studies.

Project Summary

The need for mobility originates from the spatial separation of functions and activities that creates the need for people and goods to be moved between different locations. These displacements allow to produce and to consume, but also to develop and maintain social networks … and are therefore necessary for a full participation in society. The essential role that mobility plays in this, has been increasing constantly over the last centuries and has led to the present era of hyper-mobility: our daily life consists of a growing mix of activities and locations and this network can only be kept together with an increasing number of displacements. The increase of displacements and displacement distances has led to a growth of undesirable mobility related externalities: a negative impact on health, quality of life, climate and space and landscape. In addition, the increasing number of displacements also leads to overcapacity of the mobility systems themselves. The delays and nuisances this creates, endanger the virtues of accessibility and the wellbeing of traffic participants.

To answer both the internal and the external problems, the mobility system has to become more sustainable. Only this will allow to preserve the positive role that mobility plays, without resulting in the present negative internal and external effects. The challenge for such a sustainable transition is greatest and most urgent in urban environments that are concentrations of activities and functions. Here hyper-mobility is sensed the most and the capacity of the mobility system exceeded the fastest. Because cities are the core of our socio-economic networks, the undesirable externalities of mobility are endangering the welfare and quality of life in these networks.

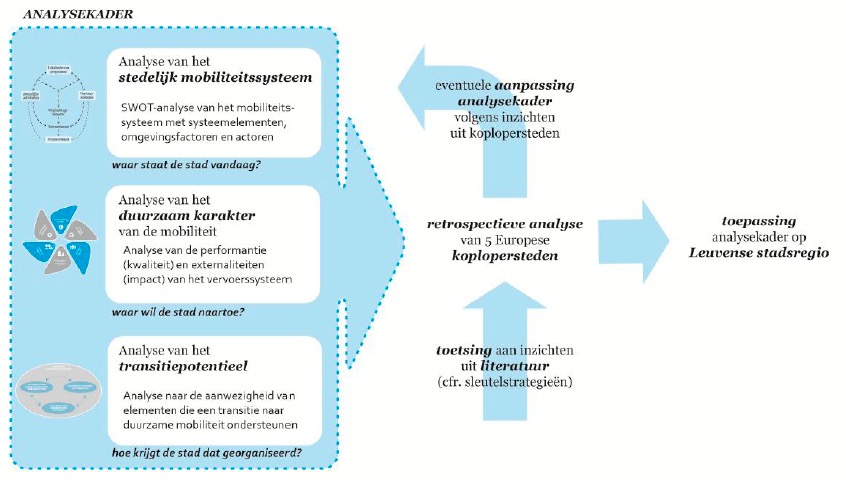

To make urban mobility more sustainable, the urban mobility system must pass through a fundamental transition. Such a transition depends on many aspects, that are difficult to map and to describe. The interrelations between transport, densely built structures, social networks, economic infrastructure … make urban mobility systems extremely complex and interventions very challenging. Therefore there is a need for an analytical framework that is able to describe existing mobility systems and investigate the potential for a transition towards a more sustainable system to happen. This research report describes the making of such an analytical framework, applied retrospectively to five European best-case cities and then to the mobility system of the Flemish city of Leuven.

The analytical framework that is presented here, starts from a fundamental approach of the three defining components that determine a ‘transition towards a sustainable mobility system in cities’. The framework functions as a filter for reading and understanding the complex urban mobility system in an intelligent and selective way. Therefore the most essential analysis aspects are listed per component, with their coherence clarified and research questions formulated to guide a critical reading of mobility in an urban region.

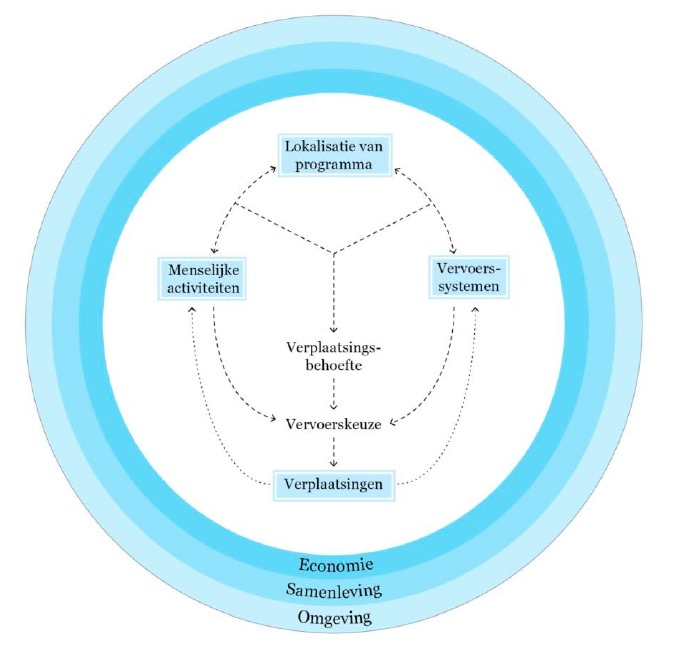

- The urban mobility system. The first component is the demarcation of the urban mobility system. This involves a trialogue between three elements: space (localisation of functions), human activities and transport systems. These three generate a need for displacements that is answered by a choice of mode. The analytical framework includes both internal system elements (e.g. the spatial structure of an urban region, the present traffic infrastructure, the human activities or the transport modes used), external environmental factors (e.g. land prices, available technology or demographic development) and actors involved (e.g. travellers, public authorities, traffic operators or inhabitants).

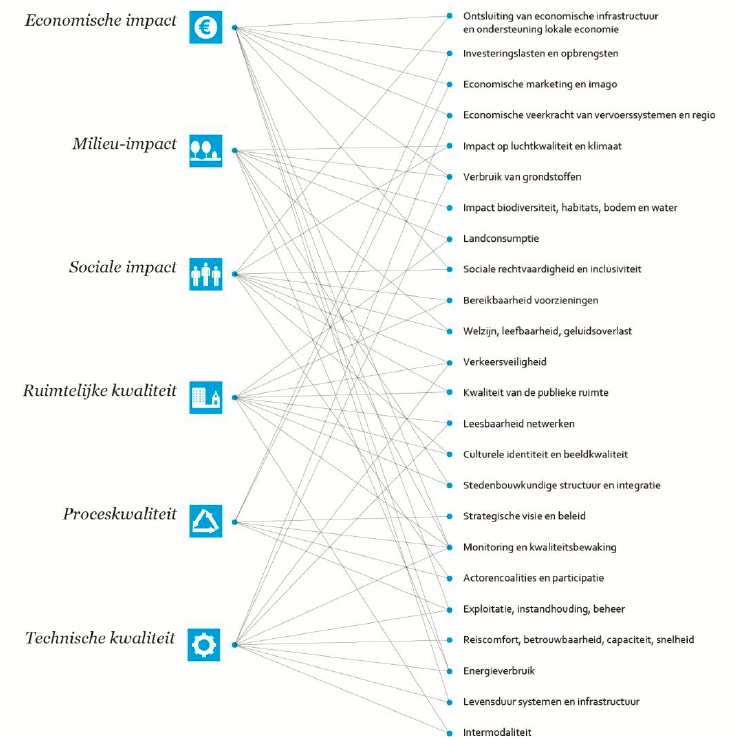

- Level of sustainability. The second component investigates the sustainable character of the urban mobility system and indicates the direction to improve its level of sustainability. Sustainability is in this context defined as a maximum enduring quality on the level of space, technology and processes, with a minimal negative impact and where possible even positive consequences on the natural environment, society and economy. This leads to six fields of sustainability, in which 24 themes are defined to summarise the sustainability of urban mobility systems. These include: economic impact (e.g. the access to economic infrastructure, investments or regional economic resilience), environmental impact (e.g. land consumption, impact on air quality or use of resources), social impact (e.g. safety, wellbeing or social justice), spatial quality (e.g. scenic quality, legibility or urban integration), process quality (e.g. quality monitoring, participation or exploitation and management) and technical quality (e.g. comfort and reliability, material quality or energy consumption).

- The potential for transition. The third component of the analytical framework investigates the transition that is necessary to make the system more sustainable and what potential exists to realize that. A transition is a comprehensive, structural change in a socio-technical system. In the analytical framework it is approached along four main axes that contain 24 research aspects: present landscape elements (relevant trends on regional and international scale), capacity for vision development (e.g. consistency in governance, presence of opinion leaders or means to create support for innovations), capacity for the support of learning infrastructure (e.g. access to knowledge sources, level of public participation or presence of trans-sectorial actor networks) and capacity for the support of niches (e.g. presence of innovative government initiatives, relations between niches and the mobility regime or means for the upscaling of niches).

This analytical framework is then used for the retrospective analysis of the sustainable urban mobility transition of five European cities, considered best cases in the field of urban mobility. This analysis allows to test the analytical framework and also shows a series of inspiring strategies and practices, including success factors and obstacles for their application. The first three cases take a full mobility system approach:

- Freiburg distinguishes itself with a very broad approach of the mobility policy, in which simultaneously is chosen for the improvement of the infrastructure for public transport, cyclist and pedestrians, but without banning cars entirely from the city centre. This is combined with innovative urban planning and development along the principles of transit oriented development and city of short routes. The transition in Freiburg was the consequence of a consequent urban policy and vision making with changing stakeholder coalition, in which the city government played a decisive role but was also supported by a strong environmentally engaged population. The result is a city in which every inhabitant enjoys a broad modal choice and car traffic counts only for 30% of urban displacements.

- Groningen focuses in its city centre entirely on cyclists and pedestrians, with bikes accounting for more than half of the inner city displacements. This is most of all a consequence of the extremely compact and multifunctional urban structure, the excellent bike infrastructure and a series of restrictive measures to keep the car traffic out of the centre. The transition took place through top-down planning measures from the city council, combined with good communication with all stakeholders. Although the traffic situation in the inner city clearly became more sustainable, this is not true for the in- and outgoing traffic in Groningen. These displacements mainly take place by car and the political will is missing to invest in strong alternatives.

- In Zürich, public transport is the central mode of the urban mobility with tram and S-Bahn forming the spine of urban development. Thanks to a wide offer and high travel comfort public transport has become a true alternative for car traffic with a share of 60% in the inner city displacements. A strong involvement of the population in decision making, a good organization of the public transport operators and the integrating of spatial planning and mobility have supported this. The focus is mainly on pull factors instead of restrictive measures. For in- and outgoing displacements this turned out insufficient, car traffic still is the leading mode here.

The last two cases have undergone a less profound transition, but have been included in the report because of their small scale and level of innovation. They show that small, intelligent measures can create a shift in the urban mobility system that with consequent support can evolve into a real transition.

- Bolzano was able to profile itself as cyclist city in a relatively short time span with a number of well-aimed infrastructural measures and a smart marketing campaign. The share of cyclists in the inner city displacements has doubled to 30%. What started as a series of ad hoc interventions is now extended into an ambitious vision on sustainable urban mobility that will be adopted further in the near future.

- La Rochelle has a longer prehistory as early adopter of many innovative mobility strategies to reduce the car pressure in its historic inner city. This includes: car free streets, rental bikes, electric rental cars, distribution shuttles and so on. Recently these numerous small projects have been integrated into one overall system that offers inhabitants and visitors a wide range of mobility options within the city centre.

The report is concluded with a proactive analysis of the Flemish city of Leuven. Here the analytical framework is used to investigate the potential in a city for a transition that makes the urban mobility system more sustainable. Based on an extensive description of the present mobility system in Leuven, of the sustainability of the urban mobility and of the present capacities for transition, nine opportunities and nine threats were identified for the transition potential.

The opportunities are:

- the present sense of urgency due to the seriousness of many mobility problems;

- the present dynamics and demographic and economic growth that can be used as leverage;

- the recently started project Leuven Climate Neutral 2030 as common awareness and mobilization project;

- the presence of the KU Leuven as defining factor in both the demographic and the economic dynamics;

- the power and stability of the city government in Leuven;

- the presence of a good basic infrastructure for road and rail;

- the strong position of the bicycle that in the short term could be part of an important modal shift;

- the need for a review of many policy visions and documents and therefore the possibility to integrate them better and make them more sustainable and finally;

- the existence of the research project Regionet Leuven as source of inspiration and exercise in intergovernmental cooperation in the urban region.

The threats identified in the report are:

- the imminent lock-in of the present unsustainable mobility system if the direction of spatial development in the region is not changed rapidly;

- the difficult position of public transport with a low public support and bad organization;

- the absence of a strong supra-local government level;

- the weak cooperation between the involved stakeholders;

- the absence of a strong learning infrastructure outside of the university;

- the fact that the spatial structure that forms the basis of the many unsustainable displacement patterns is difficult to change and only on the long term;

- the lack of means on local and regional level for new investments;

- the lack of public and political support in the city for far-reaching visions;

- the lack of experience with transition processes because of the lack of change agents that could successfully embody the needed change to sustainable mobility.

The analysis of the European case cities and the Flemish city of Leuven offers a first test of the potential of the analytical framework that is developed in this report. It aims at cities that want to make their spatial and mobility policies more sustainable and start a true transition of their urban mobility system. The framework offers them an instrument that allows to investigate the present mobility system thoroughly, define the direction of the transition and identify obstacles and opportunities for its realization. The analyses in this report are mainly based on desktop research; for the analysis of other case studies we suggest to complement this with more fundamental field research to map the spatial, political and social dynamics of the studied urban region in more detail.